Pregnancy dilemmas in rheumatologic disease

<em>Pregnant women with rheumatologic disease face dilemmascreated by their pregnancy and are at increased risk for complications.Some dilemmas are created by the medications that areused to control inflammation; others are created by disease activityor laboratory values. Dilemmas include fetal risk from receivingleflunomide and exposure to tumor necrosis factor α in pregnancy;timing and management of lupus nephritis in pregnancy; andasymptomatic elevated antiphospholipid antibodies. (J MusculoskelMed. 2008;25:190-195)</em>

Should women discontinue medications for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) when pregnant? Should they become pregnant with previous lupus nephritis? Should they risk miscarriage with positive antiphospholipid (aPL) antibodies?

Pregnant women with rheumatologic disease often face dilemmas created by their pregnancy and are at increased risk for both pregnancy- and disease-related complications. In this article, I present several cases of women who had a rheumatologic disease and were pregnant or wanted to be and offer advice and recommendations for addressing their dilemmas.

Dilemma 1: Pregnancy in a woman receiving leflunomide and etanercept for RA

A 28-year-old white woman with a 5-year history of RA calls on a Monday morning because she discovered that she is pregnant, probably about 8 weeks gestation, based on her last menstrual period. She has been taking leflunomide, 20 mg/d, plus etanercept, 50 mg/wk, for the past 2 years and has been doing well on this regimen. She asks whether she should continue her medications and, if she does,what effect they will have on her baby.

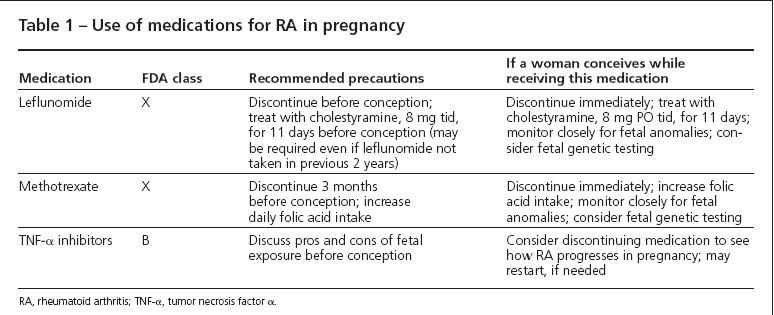

Comments. Any woman of reproductive age should be instructed not to become pregnant while taking leflunomide or methotrexate (MTX). Both medications are FDA category X (Table 1), meaning that the high potential of harm to the developing fetus outweighs any potential benefit of the drug to the mother. Leflunomide inhibits purine metabolism, interfering with DNA formation and leading to chromosome abnormalities and cell death. MTX is a dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor that decreases maternal folic acid reserves; having low folic acid levels early in pregnancy increases the risk of neural tube defects.

Table 1

With first trimester exposure, in particular, the effects of leflunomide and MTX can be devastating to a fetus.The most common birth defects among women exposed to these medications are abnormalities in the CNS, limbs, and palate, as well as cranial ossification.1 MTX often is used to abort ectopic pregnancies but in doses several times higher than typically used to manage rheumatologic disease.

The manufacturers of leflunomide and MTX recommend that these drugs be discontinued at least 3 months before conception is attempted, because both drugs have prolonged half-lives. Women planning pregnancy should take at least 1 mg of folic acid per day, although more may be prudent to ensure that stores are replenished.

If a woman has taken leflunomide within 2 years of conception, obtaining a serum leflunomide level is recommended. If the level is above 0.02 mg/L, then a course of cholestyramine is recommended to hasten clearance of the drug; 8 g of cholestyramine is administered as a drink in juice or water 3 times a day for 11 days.Taking this medication is not pleasant, but it is adequately tolerated in motivated patients.

If a pregnancy is discovered in a woman taking leflunomide, the drug should be stopped and a course of cholestyramine started immediately. There is no specific treatment available for women who conceive while taking MTX, although treatment with higher doses of folic acid is advisable.

In spite of dire warnings, not all fetuses exposed to leflunomide or MTX will be born with congenital anomalies. In fact, the majority of fetuses appear to be unaffected.

The Organization of Teratology Information Specialists study reported on 63 pregnancies in women taking leflunomide at the time of conception.2 These pregnancies were compared with 108 pregnancies in women who had RA but were not taking leflunomide with 58 pregnancies in healthy women.

The study found a similar rate of congenital abnormalities in the RA pregnancies with and without leflunomide exposure (9.3% and 13%, respectively); both rates were higher than in the healthy population (3.5%).The rate of pregnancy loss was similar for all women with RA, regardless of leflunomide exposure.The rate of preterm birth was slightly higher for women receiving leflunomide than women with RA without exposure. All women stopped the leflunomide when pregnancy was found. Most took cholestyramine when the pregnancy was discovered.

These data are similar to those from 2 other cohorts. Neither found an increase in congenital abnormalities in babies born to women taking leflunomide early in pregnancy.1

Given these data, I do not routinely suggest a therapeutic abortion for pregnant women exposed to leflunomide or MTX. I discuss the possible complications and refer the patient to a high-risk obstetrics practice for further evaluation. Genetics counselors, typically linked to obstetrical practices, may be particularly helpful in outlining potential pregnancy risks. Many patients elect to continue the pregnancy with close ultrasonographic monitoring for abnormalities. Because drugs may cause chromosomal abnormalities, chorionic villous sampling or amniocentesis should be offered.

The use of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors (infliximab, etanercept, and adalimumab) during pregnancy is more controversial. All 3 agents are FDA pregnancy class B, meaning that long-term animal data have not uncovered abnormalities. There was no evidence of increased fetal toxicity or pregnancy loss in rodents given a dose of a TNF-α inhibitor 100-fold higher than that used in humans.1

The data on human pregnancies are still emerging but look positive overall. Maternal antibodies usually are blocked from entering a developing fetus until about week 16 of gestation.3 At that point, the mother's IgG antibodies can flow into the fetus. Based on these data, it is thought that TNF-α inhibitors may not cross the placenta early in pregnancy but do so during the latter half of pregnancy. This may explain why most exposed fetuses do not have abnormalities: there may be little drug exposure in the first trimester.

Some more concerning data came to light recently-a review of the FDA adverse effects database identified 41 babies born with congenital abnormalities after TNF-α inhibitor exposure.4 The authors suggested that many of these abnormalities may be incomplete VACTERL, a syndrome of associated birth defects.The most common anomaly reported was cardiac, followed by urinary tract abnormalities and 2 infants with trisomy 21. These congenital abnormalities are the most frequently reported anomalies in US infants; whether they are associated with the VACTERL syndrome or simply common anomalies is unclear. Because the number of total pregnancies exposed to TNF-α inhibitors nationwide is unknown, determining an abnormality rate or comparing this with the general unexposed population is impossible.

Perhaps the most notorious embryotoxic medication is thalidomide, also a TNF-α inhibitor but through a mechanism different from those of the current drugs. Up to one-fourth of fetuses that have thalidomide exposure were born with a fetal abnormality.The current biologic TNF-α inhibitors clearly have a very different risk profile, but concern remains. Based on the available data, a pregnancy conceived while the woman is receiving a TNF-α inhibitor probably will result in a healthy baby. Whether the woman continues the TNF-α inhibitor therapy throughout the pregnancy should be based on her disease activity level and the potential for lasting joint damage without receiving the drug. Because many women with inflammatory arthritis improve during pregnancy, I recommend trying a period off the TNF-α inhibitor initially, leaving open the option to restart the biologic agent if arthritis flares significantly.

Dilemma 2: A woman with previous lupus nephritis receiving mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) wants to get pregnant

A 30-year-old African American woman with a history of lupus nephritis wants to have a baby; 18 months earlier, she had 5 g/24 h of proteinuria and red and white cell casts, and a renal biopsy showed World Health Organization class 4 lupus nephritis. She was treated with high-dose corticosteroids and MMF, 1.5 g twice a day. With this regimen, her proteinuria has improved to 1 g/24 h, her active urinary sediment has resolved, her creatinine level has normalized, and she has been doing well for the past 9 months. She no longer is receiving the prednisone but continues to receive MMF, 1.5 g twice a day, and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), 400 mg/d. Should she get pregnant? If so, should she continue her medications? What risks does she face during pregnancy?

Comment. Women with previous lupus nephritis often have difficult pregnancies, but many of these pregnancies result in a healthy baby and mother. The risk of pregnancy complications, including pregnancy loss, preterm birth, and preeclampsia, depends heavily on the degree of renal impairment and activity of lupus nephritis at conception.5

Avoiding pregnancy when nephritis is still active-while the urine still has cells and casts and the protein level has not decreased significantly-is very important. Active lupus nephritis during pregnancy may be disastrous for both the mother and the fetus, leading to high rates of pregnancy loss, preterm birth, and preeclampsia.

Although end-stage renal disease after pregnancy is rare, this risk is real for a woman who has active lupus nephritis that goes unmanaged for many months.5 The first recommendation is to avoid pregnancy until the nephritis is under good control, preferably in remission for at least 6 months. Decreasing both hypertension and proteinuria before conception improves the chances of delivery of a healthy baby by several-fold.6

For many young women, management of lupus nephritis with MMF has improved the chances of conception after therapy. Unlike cyclophosphamide, MMF does not appear to have any impact on fertility during or after therapy. However, MMF has been associated with a high rate of miscarriage and fetal abnormalities.

A report from the National Transplantation Pregnancy Registry identified 33 pregnancies exposed to MMF. Of these, 45% resulted in a spontaneous abortion; of the live births, 22% had a congenital anomaly and 61% were preterm.7 In response to this and several case reports, the FDA recently changed the pregnancy classification of MMF from class C (potentially dangerous) to class D (documented evidence of danger, risks may not outweigh benefits).

Therefore, when a woman with well-controlled lupus nephritis who is receiving MMF wants to get pregnant, I change her medication to azathioprine (AZA). I try to make this switch several months before pregnancy to ensure that the AZA will be effective in controlling her disease. If it is, and she continues taking this drug, she has a good chance of a successful pregnancy. Of 10 women with previously active systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) who were receiving AZA at conception, all had a live birth late in the third trimester.8

AZA also is FDA class D, but there is good documentation of this drug being relatively safe during pregnancy.The fetal liver does not contain the enzyme required to convert AZA to its active metabolite, thereby decreasing fetal exposure.5 In women taking AZA for solid transplants or inflammatory bowel disease, no increased risk of congenital abnormalities has been found.1 Women taking AZA for a previous renal transplant have a higher rate of preterm birth than the general population, but whether this is the result of the underlying disease process or of the medications used to prevent organ rejection is not clear.

All women with SLE should continue to receive HCQ during pregnancy. There is no evidence of an association between HCQ and congenital anomalies. In addition, continuation of HCQ during pregnancy can decrease the risk of SLE flare during pregnancy,9 which is particularly important for women with a history of lupus nephritis.

Women with current or previous lupus nephritis also are at increased risk for preeclampsia, hypertension, and preterm birth during pregnancy, even beyond the risks for women who have nonrenal lupus.6,10 Randomized controlled trials have provided some evidence that daily low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d) can decrease the risk of preeclampsia by 15% to 25% in women at high risk for this complication. 11 Daily low-dose aspirin did not put offspring at increased risk for congenital anomalies or long-term sequelae. Although no studies have evaluated the value of low-dose aspirin use during pregnancy in women with SLE, it may be worthwhile for women with a history of lupus nephritis or hypertension or both to start this therapy early in pregnancy.

Women with a past history of lupus nephritis warrant special monitoring during pregnancy for a recurrence of nephritis. Because some have a fixed renal defect that leads to persistent proteinuria, even in remission, assessment of proteinuria in pregnancy can be complicated. During all pregnancies, renal blood flow increases by at least 50%, leading to a mild increase in proteinuria, even from a healthy kidney.12 In women with previous renal damage, a doubling of baseline proteinuria may not signify increased lupus nephritis activity.5 Monitoring for increased red or white cell counts and casts is of particular importance.

Preeclampsia becomes a complicating factor in women with lupus nephritis in the third trimester. Preeclampsia presents with hypertension, proteinuria, and lower extremity edema, typically later in the third trimester, and may resemble a flare of lupus nephritis. Again, cell counts and assessment for urinary casts is important because preeclampsia does not present with an active urinary sediment. Looking for other signs of active lupus (eg, joint disease, rash, and hematological changes), a rising anti-double strands DNA antibody, or falling complement also may help distinguish between preeclampsia and lupus nephritis. In some situations, distinguishing between these diagnoses is impossible, necessitating management for both.

My recommendation to this patient is yes, she can get pregnant in the future, although she will be at increased risk for preeclampsia, preterm birth, and a flare of lupus nephritis during pregnancy. I would stop her MMF and start AZA, with the goal of remaining on this regimen for at least 3 months to ensure that she will remain stable, before conception. During pregnancy, both her rheumatologist and high-risk obstetrician need to monitor her closely to ensure that any signs of trouble are addressed promptly.

Dilemma 3: Pregnancy in a woman with positive aPL antibodies but no past history of pregnancy or thrombosis

A 26-year-old white woman with no previous pregnancies or thromboses was found to have an anticardiolipin (aCL) IgG antibody level of 82 GPL (highly elevated) that was elevated repeatedly at 6- month intervals. Her lupus anticoagulant, anti-β2-glycoprotein I antibodies, and aCL IgM levels are normal. She is interested in becoming pregnant but has been told that she will have a miscarriage. How do you advise her?

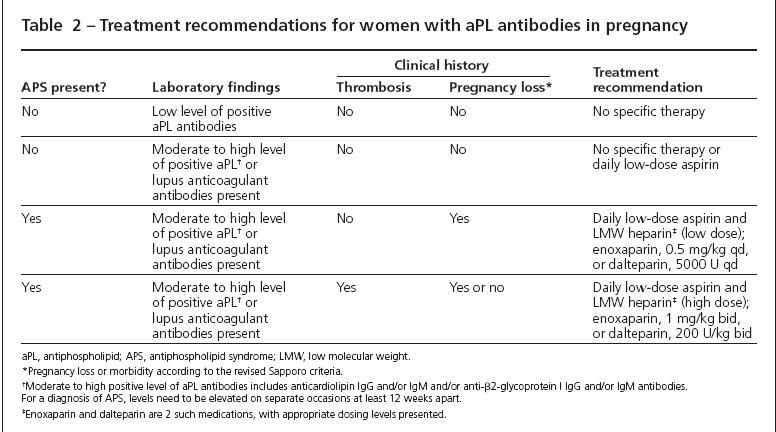

Comments. aPL antibodies are known to be associated with pregnancy loss and thrombosis. An unmanaged pregnancy in a woman with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is at 90% risk for fetal loss.13 However, simply having aPL antibodies does not provide a diagnosis of the syndrome. A patient must have both clinical (thrombosis or pregnancy mishap) and qualifying laboratory criteria to meet the diagnostic criteria for APS. This distinction is important, because the pregnancy risk for women who fully meet the criteria is markedly worse than for those women who only partially meet these criteria.

Women who have an abnormal lupus anticoagulant or other aPL antibody level may be at slightly increased risk for pregnancy morbidity compared with other women. However, the extent of this risk is subject to debate.

In the Hopkins Lupus Cohort, 66 pregnancies occurred in women with SLE who had an elevated aPL or lupus anticoagulant antibody level but did not meet the clinical APS criteria; 12% of these pregnancies resulted in a pregnancy loss, a rate identical to that for women in this cohort who had SLE but no aPL antibodies. This rate is markedly different from the 40% pregnancy loss rate in women who did fulfill the criteria for APS.6

The level of positive antibodies also is important. Many women with SLE have a low positive IgG or IgM aCL antibody level. The clinical significance of these low titers is unclear, and they probably do not pose a major threat to pregnancy viability.

Women with previous pregnancy loss and a lupus anticoagulant are at particular risk for pregnancy loss. A meta-analysis of 25 papers found that the presence of a lupus anticoagulant antibody in a woman with at least 2 previous pregnancy losses increased her risk of a subsequent late pregnancy loss by 8- to 15-fold.14

In this study, almost 7% of women with a lupus anticoagulant antibody experienced a loss after 13 weeks of gestation, compared with 0.2% of those women who did not have a lupus anticoagulant antibody or previous pregnancy loss. An elevated aCL IgG or IgM antibody level raised the risk of another pregnancy loss by 3- to 5-fold compared with healthy women.

For a young woman who does not have previous pregnancies or thrombosis, I generally do not recommend anticoagulation therapy, even if there is a positive lupus anticoagulant or aPL titer (Table 2). Daily low-dose (81 mg) aspirin may be added without significant risk of morbidity, but the benefits are unknown in this situation. For women who have infertility or are older-and therefore have fewer opportunities for pregnancy-aspirin therapy may be considered more strongly.

Table 2

Treatment with a low dose of low molecular weight (LMW) heparin may be considered. However, there is little or no evidence to confirm the benefit of this therapy in a woman who does not have the full APS syndrome.The drawbacks of potentially unnecessary heparin therapy include risk of hemorrhage, expense, bruising, osteoporosis, and daily injections.

For women with previous pregnancy morbidity and aPL antibodies, treatment with LMW heparin and daily low-dose aspirin is clearly indicated. For women without previous thrombosis, low-dose LMW heparin (0.5 mg/kg/d) with aspirin is adequate. Full anticoagulation is required for women with previous thrombosis, especially because the risk of thrombosis is increased several-fold during pregnancy.

In addition to antithrombotic therapy, closer obstetrical monitoring is recommended during pregnancy for women with APS. At Duke University, we initiate nonstress testing weekly at week 28 of gestation, then twice a week from week 32 to delivery. If abnormalities are noted prematurely, consideration should be made for an early delivery. However, there are no published guidelines delineating the optimal antenatal testing schedule.

Several randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that therapy with heparin plus aspirin can cut the risk of pregnancy loss by half in women with APS. Even with appropriate therapy, one-fourth of pregnancies in women with APS result in a pregnancy loss, a rate about twice that of the general population.15

Given these data, I would reassure this young woman that although she has an elevated aCL IgG level, she still has a very good chance of delivering a healthy baby. She may wish to take low-dose aspirin daily during pregnancy, although there is no clear evidence showing that this will be needed to have a normal pregnancy.

References:

References

- Ostensen M, Khamashta M, Lockshin M, et al. Anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive drugs and reproduction. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:209.

- Chambers CD, Johnson DL, Lyons Jones K, et al. Pregnancy outcome in women exposed to leflunomide: the OTIS Autoimmune Diseases in Pregnancy Project. Arthritis Rheum. 2006; 54(9 suppl):S250-S251.

- Simister NE. Placental transport of immunoglobulin G. Vaccine. 2003;21:3365-3369.

- Carter JD, Ladhani A, Ricca L, et al. A safety assessment of TNF antagonists during pregnancy: a review of the FDA database. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;55(9 suppl):S667.

- Germain S, Nelson-Piercy C. Lupus nephritis and renal disease in pregnancy. Lupus. 2006; 15:148-155.

- Clowse ME, Magder LS, Witter F, Petri M. Early risk factors for pregnancy loss in lupus. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(2, pt 1):293-299.

- Sifontis NM, Coscia LA, Constantinescu S, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in solid organ transplant recipients with exposure to mycophenolate mofetil or sirolimus. Transplantation. 2006; 82:1698-1702.

- Clowse ME, Witter F, Magder LS, Petri M. Azathioprine use in lupus pregnancy. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(9 suppl):S386-S387.

- Clowse ME, Magder L, Witter F, Petri M. Hydroxychloroquine in lupus pregnancy. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3640-3647.

- Clowse ME, Magder LS, Witter F, Petri M. The impact of increased lupus activity on obstetric outcomes. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52: 514-521.

- Duley L, Henderson-Smart DJ, Meher S, King JF. Antiplatelet agents for preventing preeclampsia and its complications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD004659.

- Jeyabalan A, Conrad KP. Renal function during normal pregnancy and preeclampsia. Front Biosci. 2007;12:2425-2437.

- Rai RS, Clifford K, Cohen H, Regan L. High prospective fetal loss rate in untreated pregnancies of women with recurrent miscarriage and antiphospholipid antibodies. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:3301-3304.

- Opatrny L, David M, Kahn SR, et al. Association between antiphospholipid antibodies and recurrent fetal loss in women without autoimmune disease: a metaanalysis. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2214-2221.

- Branch DW, Khamashta MA. Antiphospholipid syndrome: obstetric diagnosis, management, and controversies. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:1333-1344.