Managing Musculoskeletal Issues in Lupus: The Patient’s Input Invited

ABSTRACT: About half of patients with systemic lupus erythematosusexperience musculoskeletal involvement: arthritis, arthralgia,myalgias,myositis, tenosynovitis, fibromyalgia, or osteonecrosis. Patientswith arthritis often have symmetrical large- and small-joint polyarthritisunassociated with radiographic evidence of erosive or deformingdisease.Treatment generally focuses on anti-inflammatoryagents, such as NSAIDs and corticosteroids. Antimalarials are commonlyused. When NSAIDs prove ineffective, limited use of corticosteroidsmay help, but patients need to be informed of the adverseeffects. Antimalarial agents usually are recommended for all personswith lupus arthritis. Shared decision making can allay concernsabout drug toxicity and adverse effects and encourage compliancewith treatment. (J Musculoskel Med. 2008;25:458-463)

ABSTRACT: About half of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus experience musculoskeletal involvement: arthritis, arthralgia, myalgias, myositis, tenosynovitis, fibromyalgia, or osteonecrosis. Patients with arthritis often have symmetrical large- and small-joint polyarthritis unassociated with radiographic evidence of erosive or deforming disease. Treatment generally focuses on anti-inflammatory agents, such as NSAIDs and corticosteroids. Antimalarials are commonly used. When NSAIDs prove ineffective, limited use of corticosteroids may help, but patients need to be informed of the adverse effects. Antimalarial agents usually are recommended for all persons with lupus arthritis. Shared decision making can allay concerns about drug toxicity and adverse effects and encourage compliance with treatment. (J Musculoskel Med. 2008;25:458-463)

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is widely regarded among rheumatologists as the prototypical autoimmune disorder. An estimated 250,000 persons in the United States-mostly women of childbearing age-are affected with lupus.1 Treatment is directed at mitigating damage with immunosuppressive agents, which dampen the formation of autoantibodies and immune complexes, and controlling symptoms related to the immune-mediated effects of the disease on specific organs.

Shared decision making, which refers to the collaborative effort between the patient and physician, helps determine a course of management when no best treatment option is available. This process may be especially challenging in the setting of a disease like lupus, because there are few "hard" data from the published literature to guide physicians as they formulate the patient's treatment plan. In shared decision making, the principal dynamic shifts from a physician-focused approach to diagnosis and treatment to a patient- and physician-focused approach. Presenting the patient with choices may give him or her a greater sense of control when confronting a somewhat uncommon chronic illness that has no known identifiable cause and no well-documented, widely prescribed course of treatment.

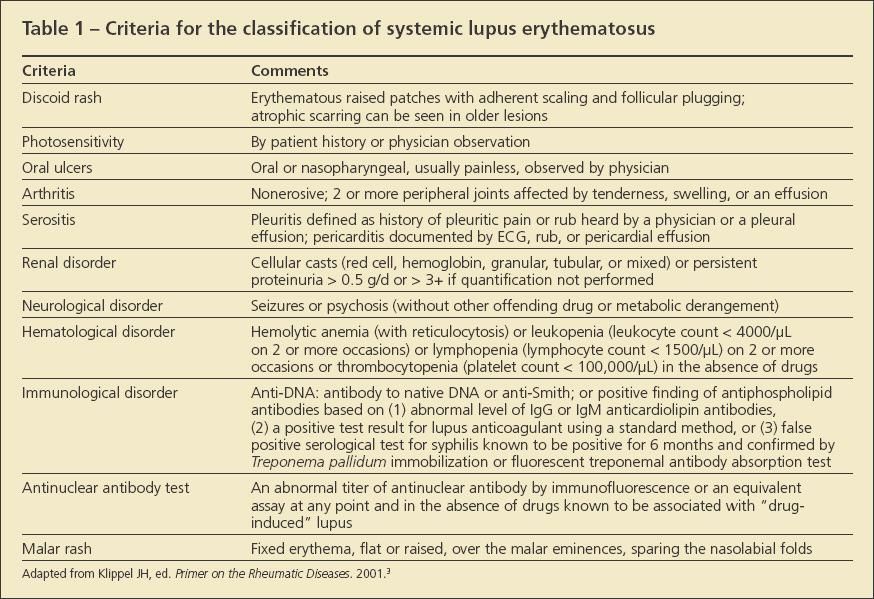

In this article, I review treatments often used to manage problems of the musculoskeletal system, which affect between 50% and 90% of patients with SLE.2 Although arthritis, arthralgia, myalgias, myositis, tenosynovitis, osteonecrosis, fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS), and osteoporosis all are musculoskeletal problems affecting patients with lupus, only arthritis-defined as non-erosive tenderness, swelling, or effusion in 2 or more peripheral joints-is included in the classification criteria for lupus (Table 1).3 At various points throughout the text, I offer insights into how you might incorporate shared decision making into the overall management protocol.

ARTHRITIS AND ARTHRALGIA

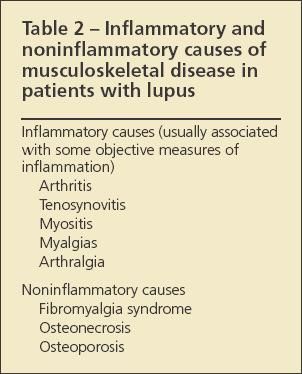

Identifying the specific cause of musculoskeletal pain in a patient with known or suspected SLE can be challenging. A leading question to answer, because it affects the approach to treatment, is whether the cause of pain is noninflammatory or inflammatory (Table 2). Findings associated with ongoing disease and inflammation include such objective signs as synovitis, joint swelling, and muscle inflammation with possible weakness, as well as certain laboratory abnormalities, chiefly, elevated values for erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP) level, and double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) level.

Patients with lupus often may have symmetrical large- and small-joint polyarthritis. Although they typically present with joint pain, they may have little demonstrable synovitis and do not have radiographic evidence of erosive or deforming disease.4 Jaccoud arthropathy, which is a deforming arthropathy associated with reducible deformities, can also be seen. Complaints of pain and the presence of synovitis signify ongoing disease activity. This sometimes is associated with serological markers of disease activity: worsening leukopenia, normochromic anemia, hypocomplementemia, and an increasing level of anti-dsDNA antibodies. The patient also may have extra articular manifestations of lupus-rash, myalgia, oral ulcers, and clinically significant renal disease.

Additional causes of arthritis to consider in the differential diagnosis include other rheumatologic diseases that affect large and small joints, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and Sjgren's syndrome, and bacterial/viral arthritides, including infectious mononucleosis, parvovirus B-19, acute hepatitis B infection, and rheumatic fever. Hepatitis C is also associated with arthralgias.

Shared decision making. The patient and physician can work through the diagnosis and management of lupus arthritis together. Because the physical signs of lupus synovitis may be subtle-less pronounced than occurs in RA, for instance-the diagnosis may be difficult to establish. The presence of extra-articular disease is another factor to consider when choosing treatment.

Anti-inflammatory medications

NSAIDs and corticosteroids often are prescribed for patients with lupus-related joint pain, sometimes along with an adjunctive analgesic. However, NSAIDs are not immunosuppressive and therefore do not attack the fundamental immune issues that cause the clinical findings associated with ongoing disease.5

Shared decision making. Because no particular NSAID has documented superiority over another in controlling joint disease in SLE, the choice of medication may be influenced by patient preferences. Points to consider include frequency of administration, availability of multiple dosage ranges, potential adverse effects, and costs of copayments for various tiered medications. Some patients may prefer capsules over tablets, liquids over pills, or enteric-coated over non–enteric-coated NSAIDs. An NSAID with a shorter half-life, such as ibuprofen, needs to be taken more frequently than one with a longer half-life, such as piroxicam. If the patient will be taking an NSAID long-term, consider prescribing lansoprazole, esomeprazole, or a proton pump inhibitor to protect against ulcers. Also, some NSAIDs, such as nabumetone and celecoxib, might offer more GI protection than others.

Corticosteroids

When NSAIDs do not control symptoms, are contraindicated, or are not tolerated, low doses of corticosteroids are an option (narcotics and analgesics do not effectively control inflammation). Methylprednisolone may cause less salt retention and be better tolerated than prednisone. The rheumatologist needs to determine the dosage and duration of treatment but usually prescribes the least amount of corticosteroid for the shortest time possible to avoid adverse effects. In addition, emerging evidence suggesting a possible link between corticosteroids and increased cardiovascular morbidity in persons with SLE makes these drugs, in essence, a "modifiable" risk factor.6

Bone loss occurs quickly and rapidly during corticosteroid therapy. To prevent this, consider bisphosphonate therapy (alendronate, risedronate, ibandronate, zoledronic acid, and intravenous pamidronate have been studied but not compared directly) for patients taking 5 mg/d or more of prednisone (or its equivalent) for 3 months or longer.7 Calcium,1000 to 1500 mg/d, and vitamin D, 800 IU/d, should be prescribed at the outset of corticosteroid therapy, along with weight-bearing exercise; 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels should be checked and treatment with vitamin D replacement given to bring the serum level to 730 ng/mL. The patient should then be maintained on 800 to 1000 IU/d.

Shared decision making. Patients often have many questions when contemplating treatment, and the decision of whether to start corticosteroids for such non–life-threatening issues as arthritis might not be clear-cut. In addition, rheumatologists may differ in their approach to treatment. The patient should be advised of the potential adverse effects of corticosteroid therapy, including weight gain; cataract formation; glucose intolerance; proximal muscle weakness; striae; osteoporosis; and susceptibility to infection, glaucoma, acne, and hypertension. Once the patient is informed about the risks and benefits of taking corticosteroids, decisions about treatment may be shared between the physician and patient.

Antimalarial agents

The antimalarial agents work through immunological, anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative, and hormonal pathways to counteract the underlying processes that lead to joint inflammation.8 They are especially effective for relieving the joint pain of SLE, often are prescribed in conjunction with NSAIDs or corticosteroids, and may be corticosteroid-sparing.5 Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine are especially beneficial for managing the cutaneous and arthritic manifestations of lupus.8

The decision to begin antimalarials may be triggered by a new diagnosis, regardless of the system or systems affected, or by specific joint or skin disease. Evidence showing increased risk of flare after antimalarials are discontinued has prompted the rheumatology community to recommend general use of antimalarials for all patients with SLE, unless otherwise contraindicated.9,10 Retinal toxicity associated with hydroxychloroquine is rare with doses lower than 6.5 mg/kg. Annual/biannual eye examinations that include visual field testing are important to monitor patients for subclinical evidence of retinal damage.

Shared decision making. Initial fears about antimalarial toxicities may be allayed by informing the patient of the relative risks and benefits. It can also help share the information gleaned from hydroxychloroquine withdrawal studies showing that the use of antimalarials helps prevent flares.

Immunosuppressive and biologic agents

Continued joint inflammation despite treatment with NSAIDs or low-dose corticosteroids may be an indication for other immunosuppressive agents, such as methotrexate (MTX), azathioprine, leflunomide, and mycophenolate mofetil. Although these agents have not been FDA-approved for the treatment of lupus, they are widely used for various manifestations of disease. Treatment should be initiated by a clinician experienced with their use and knowledgeable about their role in autoimmune disorders.

Anti–tumor necrosis factor α therapies are not FDA-approved for SLE and have been associated with the development of drug-induced lupus.11 Rituximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody directed against CD-20–positive B cells, recently was found to be ineffective in patients with moderate to severe SLE activity, despite background immunosuppressive therapy.12 Trials of other anti–B-cell therapies and other biologic agents are in progress.

An arthritis flare-up might not be associated with hypocomplementemia or an elevation of dsDNA level. Acute phase reactants, such as CRP level and ESR, may correlate with disease activity. Measurements of complement (C3, C4, CH50), dsDNA level, and the ESR/ CRP level may help guide diagnosis and treatment but should not determine the course of treatment of lupus arthritis.

Shared decision making. When arthritis is refractory to other treatments, the patient and physician might want to decide together whether to institute corticosteroid-sparing immunosuppressive agents. Discussions should include a balanced consideration of benefit versus risk for these various drugs. Physicians should be as clear to patients as possible about their expectations for a symptomatic response and a reduction in corticosteroid dependency.

Starting MTX or leflunomide may present special challenges when considering lifestyle choices because alcohol consumption should be eliminated or greatly reduced when either medication is taken. This should be factored into deciding how to manage NSAIDs-or antimalarial-refractory arthritis that is related to lupus. In addition, the use of these immunosuppressives in women of childbearing age warrants special attention to personal wishes regarding pregnancy because both drugs are contraindicated in pregnancy. Both drugs can be used in women of childbearing age provided adequate birth control is used because teratogenicity is seen with both drugs. MTX should be stopped for at least 2 full menstrual cycles before trying to conceive, and birth control should be taken in the interim. Elimination with cholestyramine is recommended for women taking leflunomide who may wish to become pregnant, and birth control should be used in the interim. Serum levels of leflunomide should be measured before attempting conception, and they should be zero.

TENOSYNOVITIS

Inflammation of the tendon sheath is common in persons with SLE, although tendon rupture is uncommon. Tenosynovitis is managed with some of the same medications that are given to control arthritis and arthralgia. Local corticosteroid injections of the flexor tendon sheaths may provide excellent symptomatic relief in the appropriate patient.

Patients with local inflammation-flexor tenosynovitis, for instance-might feel more comfortable when the area is immobilized in a splint. Systemic corticosteroids are generally not used for localized, soft tissue disorders such as this. Serological measurements of disease activity may be helpful for assessing tenosynovitis and may serve as a guide in overall management.

Shared decision making. The patient and physician should discuss the risks and benefits of the available oral treatments. This includes consideration of the relative risks/ benefits of splinting versus corticosteroid injections.

MYALGIAS AND MYOSITIS

SLE may cause muscle inflammation that is associated with pain, objective weakness, and increased levels of muscle enzymes. Far less common is severe proximal muscle weakness, similar to that of polymyositis or dermatomyositis. When the patient has muscle weakness, it remains important to rule out other causes of weakness, including thyroid disease and chronic corticosteroid use.Colchicine and statin drugs also can cause myalgias, which are generally reversible on discontinuation of the drug.

Patients with low-level myalgias and no weakness may be treated with NSAIDs. When myositis is associated with weakness, high-dose corticosteroids generally are necessary. Keep in mind that corticosteroids also cause proximal muscle weakness but no increase in muscle enzyme levels. Hydroxychloroquine also may cause reversible myopathy. Immunosuppressive agents are an alternative for patients with lupus myositis needing treatment with a corticosteroid-sparing agent.

Proximal muscle–strengthening exercises may be appropriate for patients with inflammatory disease. They are critical for those with corticosteroid-induced myopathy.

Shared decision making. The patient and physician can discuss the risk-benefit profile of the different immunosuppressive agents that can be used to treat myositis and that there may not be one "best treatment."

OSTEONECROSIS

Between 3% and 30% of patients with SLE have osteonecrosis. Persons at greatest risk for osteonecrosis include those who are taking prednisone at a dosage exceeding 20 mg/d.13 Raynaud's phenomenon and hyperlipidemia are also risk factors. Although osteonecrosis occurs most often in association with corticosteroid use, evidence suggests an association with cytotoxic drug use and antiphospholipid syndrome.14,15

Osteonecrosis often involves the large joints, such as the hip and knee, although the shoulder, femoral condyle, and small joints of the hands are not off limits. Osteonecrosis or infection should be considered in the differential diagnosis when patients with SLE present with large-joint pain or swelling. Physical findings in osteonecrosis usually are nonspecific. MRI remains the imaging study of choice for early detection of osteonecrosis.

Treatment options depend on the site affected; they range from conservative to aggressive measures. For patients with knee or hip involvement, such conservative measures as unloading and analgesics may be worth a trial but will not prevent long-term damage or the need for joint replacement.

Some evidence suggests that bisphosphonates may delay the progression to joint replacement, although this has not been confirmed in placebo-controlled, double blinded trials.The benefits of core decompression, which "decompresses" intraosseous pressure, remains controversial despite some randomized trials showing that it alleviates pain.16 Joint replacement provides patients with long-term symptomatic and functional relief.

Shared decision making. The physician can discuss these various treatment options with the patient. An orthopedic referral can also be discussed.

FIBROMYALGIA

FMS-like symptoms generally are not considered related to primary autoimmune mechanisms in patients with SLE. Symptoms may occur in the setting of a generalized flare that does not primarily affect the musculoskeletal system.

FMS may be managed with a combination of physical and pharmaceutical measures. Restoration of normal sleep and an aerobic exercise program may help the patient feel better.17 Corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive therapies are not indicated. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) may help with sleep disturbance and are effective for alleviating pain.18 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, given alone or in combination with TCAs, also have been shown to be of benefit.19 Pregabalin has been FDA-approved for the treatment of fibromyalgia and can be considered, although cost will need to be factored in.

Shared decision making. Educating patients about the scientifically proved benefits of exercise for the treatment of FMS is critical. Restoration of sleep is also important in alleviating FMS-related pain.

SUMMARY POINTS

• In shared decision making, the patient and physician collaborate to decide on treatment options. This is an evolving trend in medical care.

• Because no particular NSAID has documented superiority over another for controlling joint disease in systemic lupus erythematosus, the choice of medication may be influenced by patient preferences.

• Presenting the patient with choices may provide him or her with a greater sense of control when confronting a relatively uncommon chronic illness that has no known identifiable cause and no well-documented, widely prescribed course of treatment.

References:

References

- 1. Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:778-799.

- 2. Wallace DJ. The musculoskeletal system. In: Wallace DJ, Hahn BH, eds. Dubois’ Lupus Erythematosus. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Williams and Wilkins; 2002:629-644.

- 3. Klippel JH, ed. Primer on the Rheumatic Diseases. 12th ed. Atlanta: The Arthritis Foundation; 2001:638.

- 4. Schur PH, ed. The Clinical Management of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1996:63-84.

- 5. Williams HJ, Egger MJ, Singer JZ, et al. Comparison of hydroxychloroquine and placebo in the treatment of the arthropathy of mild systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:1457-1462.

- 6. Petri M, Lakatta C, Magder L, Goldman D. Effect of prednisone and hydroxychloroquine on coronary artery disease risk factors in systemic lupus erythematosus: a longitudinal data analysis. Am J Med. 1994;96:254-259.

- 7. American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis. Recommendations for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: 2001 update. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1496-1503.

- 8. Wallace DJ. Antimalarial therapies. In: Wallace DJ, Hahn BH, eds. Dubois’ Lupus Erythematosus. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Williams and Wilkins; 2002:1149-1172.

- 9. The Canadian Hydroxychloroquine Study Group. A randomized study of the effect of withdrawing hydroxychloroquine sulfate in systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:150-154.

- 10. Rothfield N. Efficacy of antimalarials in systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Med. 1988;85(suppl 4A):53-56.

- 11. Costa MF, Said NR, Zimmermann B. Drug-induced lupus due to anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agents. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2008;37:381-387.

- 12. Press release: Genentech and Biogen Idec announce top-line results from phase II/III clinical study of rituxan in systemic lupus erythematosus. April 29, 2008. http://www.gene.com/gene/news/press-releases/display.do?method=detail&id=11247. Accessed September 16,2008.

- 13. Cozen L, Wallace DJ. Risk factors for avascular necrosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:188.

- 14. Mok MY, Farewell VT, Isenberg DA. Risk factors for avascular necrosis of bone in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: is there a role for antiphospholipid antibodies? Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59:462-467.

- 15. Calvo-Alén J, McGwin G, Toloza S, et al; LUMINA Study Group. Systemic lupus erythematosus in a multiethnic US cohort (LUMINA), XXIV: cytotoxic treatment is an additional risk factor for the development of symptomatic osteonecrosis in lupus patients: results of a nested matched case-control study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:785-790.

- 16. Koo KH, Kim R, Ko GH, et al. Preventing collapse in early osteonecrosis of the femoral head. A randomised clinical trial of core decompression. J Bone Joint Surg. 1995;77B:870-874.

- 17. Busch A, Schachter CL, Peloso PM, Bombardier C. Exercise for treating fibromyalgia syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(3):CD003786.

- 18. Goldenberg DL, Felson DT, Dinerman H. A randomized, controlled trial of amitriptyline and naproxen in the treatment of patients with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:1371-1377.

- 19. Goldenberg D, Mayskiy M, Mossey C, et al. A randomized, double-blind crossover trial of fluoxetine and amitriptyline in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:1852-1859.