Effective Decision Making for Ankylosing Spondylitis

The signs and symptoms can be controlled with early diagnosis and treatment.

Early diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and prompt institution of treatment can control its signs and symptoms. However, early diagnosis presents clinicians with a challenge because radiographic changes-the hallmark of the disease-tend to take about 7 to 10 years to develop. Sound decision making and patient interaction, such as with screening questionnaires, can help the diagnosis and result in more effective treatment.

AS is the prototype of a group of inflammatory arthritides characterized by involvement of the axial skeleton and the absence of seropositivity for antibodies, such as rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies.1 Clinically recognizable subtypes grouped under the heading of seronegative spondyloarthritides also include reactive arthritis, arthritis associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), and undifferentiated spondyloarthritis (SpA). A common feature is the tendency to involve the sacroiliac joints, large joints of the lower extremities, attachment sites of tendons and ligaments (enthesitis), and the body's skin and mucous membranes. The seronegative spondyloarthritides are thought, incorrectly, to be less common than rheumatoid arthritis. However, they may be underdiagnosed and go unrecognized as chronic back pain or possible degenerative joint disease.

Advances in MRI have helped the diagnosis of AS before radiographic changes set in. Another clue to the diagnosis is the tendency of AS to occur within families and share some genetic markers among those who are affected. In addition, primary care physicians often see patients with back pain or diffuse body pain; recognizing features of inflammatory back pain (IBP), which is common in AS, provides an important clue to proceed with diagnostic testing. Screening patients for AS is another important diagnostic tool.

In this article, we offer a clinical case scenario of a patient with AS. We use it to explore the 5 key questions that are involved in AS diagnosis and treatment decision making.

1. When should the primary care physician consider the presence of AS or the related diseases?

Clinical case scenario. Robert, a 24-year-old college student, was seen in the student health center with symptoms of low back pain (LBP) that had been present for about 2 weeks. The pain was present in the buttocks area and alternated from the right side to the left.The pain worsened at night and occasionally forced Robert to get out of bed and walk around. He also complained of stiffness in his lower back, especially in the first 2 hours after he arose from bed in the morning. The back pain and stiffness improved after progressive activity during the day.

Robert reported that he had had this back pain twice during the previous 6 months and attributed the previous episodes to athletic activity. He took over-the-counter ibuprofen and had significant pain relief. His review of systems was negative for recent bowel or genitourinary infections, and he denied any abdominal pain, diarrhea, or fever.

Robert's family history does not show any history of inflammatory arthritis of the spine. His physical examination results were unremarkable except for tenderness over the lower back on flexion. No restriction was present when he underwent a modified Schober test or when chest expansion was measured.

The modified Schober test was performed by measuring the increase in length, while bending forward maximally, of an imaginary vertical line between 2 points placed 10 cm apart, the first at the midpoint between the dimples of Venus (corresponding to the lumbosacral junction) and the second 10 cm vertically above it in the midline. The measurement was 7 cm (normal, more than 5 cm).The maximal chest expansion on inspiration was measured at the level of the nipples; it was 6 cm (normal, more than 5 cm).

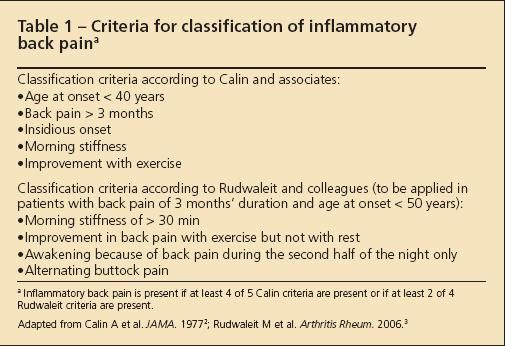

Clinical signs and symptoms of AS and the related diseases. The patient presented with the classic symptoms of IBP, a common early symptom of AS and the related diseases when they involve the spine. The characteristics of IBP are outlined in Table 1.2,3 Because the incidence of IBP is about 15% in young, healthy adults who exercise, the presence of IBP alone is insufficient to make the diagnosis of AS.

Table 1

Table

Table

Table

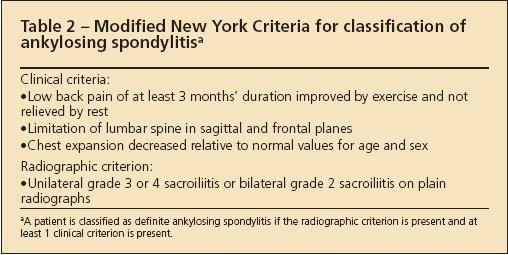

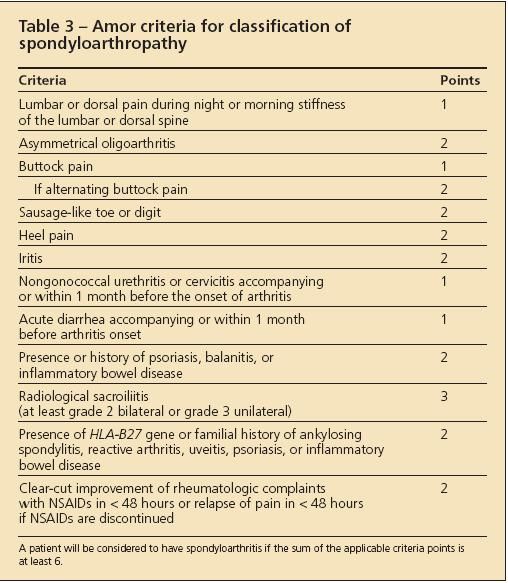

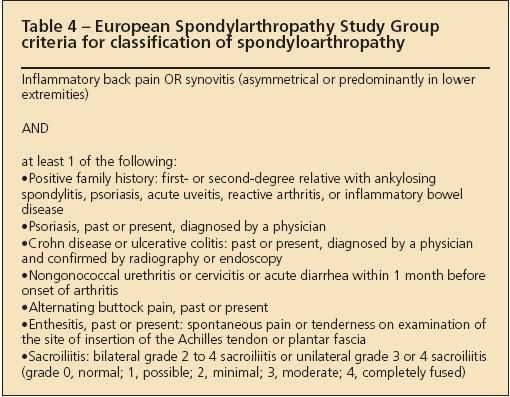

Various criteria have been developed to classify patients as having AS or SpA for research purposes (Tables 2, 3, and 4).4-6 These criteria are not useful for the diagnosis of an individual patient because they lack the sensitivity required to identify the disease reliably at an early stage.

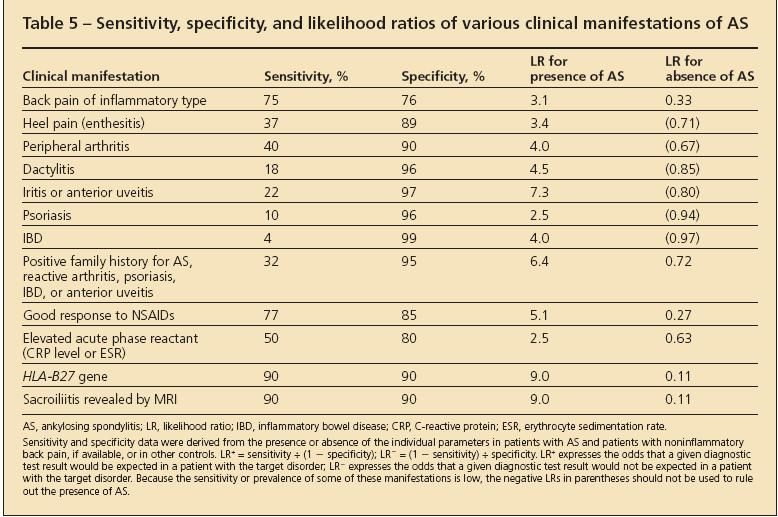

Other symptoms and signs need to be present before a physician can be confident that the patient has AS.7 These symptoms and signs vary in their ability to predict whether AS is present (Table 5).The disease also may present with many other symptoms,either as the initial symptom or in association with spinal pain.

Table 5

In some situations, a patient may present with swelling and pain in a few large joints in the lower extremity as the first symptoms. Swelling of an entire digit in a hand or foot, known as a sausage toe, may be the initial symptom. Tenderness at attachment sites of tendons and ligaments, such as the Achilles tendon and plantar fascia, is common. Involvement of the sacroiliac joint on x-ray films and of the lumbar spine may occur later; if so, the patient is classified as having AS. Lack of involvement of these areas and the absence of psoriatic rash or IBD classifies the patient as having undifferentiated SpA.

Other important symptoms to ascertain in the patient's history are recurring eye redness suggestive of uveitis and a family history of AS, psoriasis, PsA, or IBD. Another characteristic feature is that at least 50% of the joint pain and stiffness symptoms present are relieved with the use of NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen and naproxen.8

For some patients, physicians may arrive at a clinical diagnosis with a good history taken along with the presence of clinical findings, such as restricted mobility, swollen joints or fingers, psoriatic rash, or clinical symptoms of Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis. For most patients, other tests need to be performed to support the clinical findings suggestive of SpA, especially when the disease is in the early stages.

2. How do you make a diagnosis of AS in patients who have the appropriate symptoms?

Clinical case scenario. Because Robert had no signs of restricted spine mobility on examination and no specific signs of other forms of SpA, his physician decided to obtain laboratory and imaging studies. Results of a routine blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and chemistry panel were normal. The result of an HLA-B27 gene test was positive, but an imaging study of the sacroiliac joints using a Ferguson view was negative for sclerosis or sacroiliac joint erosions.

There was no confirmation of the illness even though the HLA-B27 test result was positive. Therefore, Robert's physician ordered an MRI scan with short tau inversion recovery (STIR) images (fat-suppressed images) of the sacroiliac joints.The MRI scan demonstrated edema on the ilial aspect of the sacroiliac joint on the right side consistent with the early inflammation of sacroiliitis of SpA. His physician was then confident that the patient had an SpA, but he was hesitant to call it AS because the characteristic erosive changes on x-ray films necessary to classify a patient as having AS were not present. The physician labeled the patient as having preradiographic AS.

Clinical investigations performed to establish the diagnosis of AS and the related illness. Blood tests currently available may help establish the diagnosis. Although the ESR and C-reactive protein level may be elevated in AS, that is not the rule, and these tests are not useful for screening.9

Most studies show that the prevalence of the HLA-B27 gene in white patients with AS is between 70% and 90%.10 However, because the gene is present in up to 8% of the white population and only about 0.5% to 1% of persons in the United States have AS, it follows that up to 23 million HLA-B27– positive patients do not have SpA.

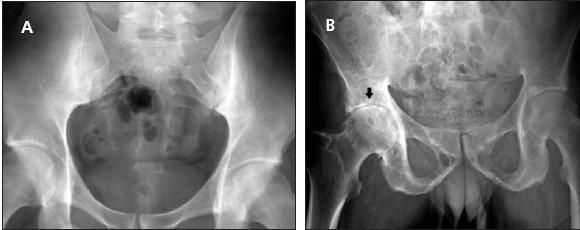

Therefore, there is a greater chance that the presence of the HLA-B27 gene represents a false positive test result in the general population and in patients who have mechanical back pain. However, in the combination of the presence of IBP and the HLA-B27 gene, the individual patient has a 59% chance that he or she has AS.9 Therefore, the presence of IBP and a positive test result increase the likelihood ratio to a clinically significant level for a specific patient having AS. Erosions and sclerosis in the sacroiliac joints (Figure 1) take up to 10 years to evolve.Therefore, they are not useful for establishing the disease when a patient has AS in the early stages.9

Figure

An MRI scan of the sacroiliac joints with fat-suppressed images (Figure 2) can clearly show evidence of inflammation, which is a specific way to establish the diagnosis. In some patients, the disease may begin in the thoracolumbar spine. Therefore, a similar MRI protocol may be needed in this area using T1 and STIR images to look for inflammation in the facet joints or along the vertebral edges (Romanus lesions).

Figure 1 –

A conventional radiograph of the pelvis of a 32-year-old man with stage II/III ankylosing spondylitis shows bilateral sacroiliitis (A). In another patient, a 50-year-old man with advanced disease, both sacroiliac joints are fused (B). In addition, inflammatory arthritis affects the right hip joint (arrow).

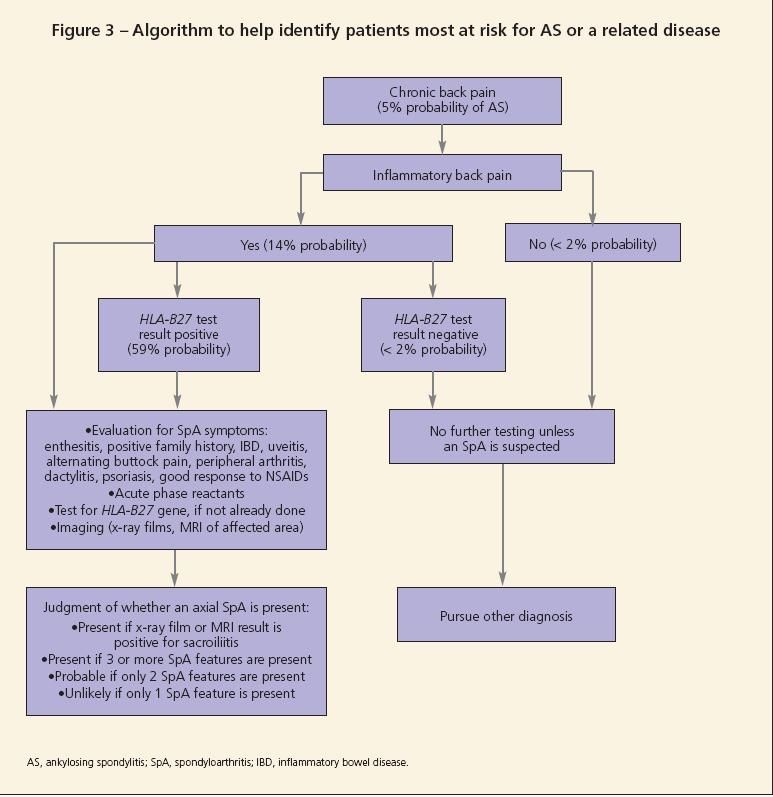

Symptoms of IBD should prompt referral for the performance of an endoscopy or colonoscopy to establish the disease. Figure 3 shows an algorithm that may be followed to establish the diagnosis of either preradiographic AS or an SpA.11

Figure 2 –

An MRI scan with short tau inversion recovery sequence of the sacroiliac joints is shown here. The dotted arrows show bone marrow edema in the left sacroiliac joint, which indicates that active sacroiliitis is present. The solid arrows show areas of sclerosis in the right sacroiliac joint, which indicate that chronic sacroiliitis is present.

3. What is the familial risk for AS and are women affected differently than men?

Clinical case scenario. Robert's family accompanied him to his visit to the rheumatologist. His mother was concerned about the risk of AS in her 3 younger children (daughters aged 17 and 19 years and a son aged 14 years). Her other children had no LBP or stiffness. Her 17-year-old daughter had had an evaluation for chest wall and upper back pain, which was attributed to stress. The rheumatologist assessed the risk of AS and the related diseases in the family to be about 20%. He recommended that the 17-year-old daughter have an MRI scan of the thoracic spine with views of the costovertebral joints, because they often are the initial sites of involvement in women affected by AS.

Clinical and genetic features of AS. The genetic contribution to this disease has been estimated to be 90%.12 About 40% of that risk is contributed by the presence of the HLA-B27 gene. About 25% of the remaining genetic risk is thought to occur because unknown polymorphisms of 2 recently discovered genes are present, the interleukin 23 receptor gene and the ARTS1 gene.13 The rest of the risk is thought to result from environmental factors.

The sex ratio for AS was thought to be skewed 10 to 1 with a significant predominance of men. As better diagnostic modalities have become available, the male to female ratio is thought to be about 3 to 1.

Women with AS may differ in their initial presentation.14 They may have more peripheral joint, upper spine, and costovertebral joint involvement, but they may progress to having severe spine involvement similar to that in men. Juvenile-onset disease may occur in patients younger than 18 years.15 Patients often present with peripheral joint disease and only later progress to spine involvement.

4. What are the accepted therapies for patients with varying degrees of disease severity?

Clinical case scenario. Robert's primary care physician prescribed ibuprofen, 800 mg 3 times a day, and advised him to participate in stretching exercises supervised by a physical therapist. Although the symptoms of pain and stiffness improved significantly at first, the ibuprofen was not helping after 6 months. The physician switched the patient to indomethacin, 50 mg 3 times a day; this agent was not successful after 3 months.

Robert returned to the rheumatologist to consider other treatment options.His rheumatologist recommended a tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitor. Robert chose a biweekly self-injection treatment option for his AS. A skin test was performed for tuberculosis, and the results were negative. A detailed history found no exposure to infections.

Robert started the treatment regimen and continued with the stretching exercises. He experienced marked symptom relief at 6 weeks, and it continued even a year after he started the treatment.

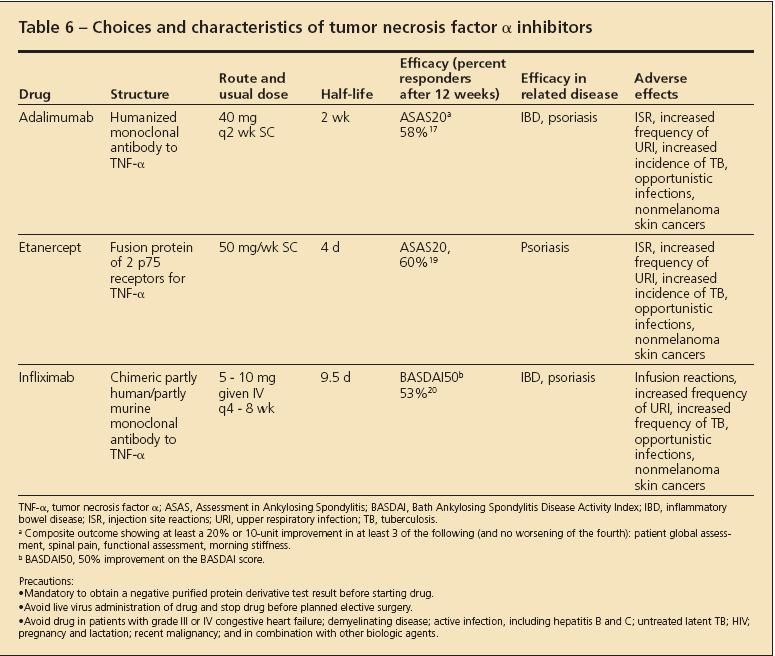

Treatment of patients who have AS with NSAIDs or biologic agents. About 50% of patients with AS can control their joint and spine pain and stiffness with daily use of an NSAID.9 The remaining 50% of patients require the use of a stronger agent, such as a TNF-α inhibitor. Some of these agents and their dosage, frequency, and adverse effects are described in Table 6.16

Table 6

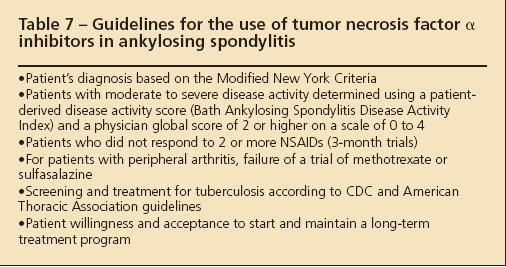

Some patients with AS have symptoms of psoriasis or IBD. These conditions need to be assessed separately and should be managed with an agent that covers both the spinal pain and inflammation and the extraspinal manifestation. The influence of the biologic medication on the extraspinal manifestation is shown in Table 6. Some patients with AS and peripheral arthritis can manage their pain well with the addition of methotrexate (MTX) or sulfasalazine, although there is less evidence of their efficacy than for the biologic agents. Monitoring patients who are receiving biologic agents and MTX involves watching carefully for infections, including opportunistic infections, and stopping the respective treatment temporarily until the infection is adequately managed and resolved. Guidelines have been published for choosing appropriate patients for the prescription of TNF-α inhibitors (Table 7).

Table 7

5. What options are available for patients who have complete fusion and have a severe spinal flexion deformity?

Clinical case scenario. Further inquiry into Robert's family history revealed that a distant relative of his father had had spinal arthritis resulting from AS for more than 30 years and that severe spine deformities had developed with a fixed flexion deformity of the thoracic and lumbar spine.The relative had consultations with rheumatologists and spine surgeons to discuss various treatment options. Overthe previous 6 months, the pain in the relative's spine had improved dramatically with the use of intravenous infusion therapy with a TNF-α inhibitor.The fixed flexion deformity of the relative's spine has not changed, and various surgical treatment options have been recommended.

Treatment of patients who have AS with advanced stages of illness and deformity. Fusion of the vertebral column and a fixed flexed posture in the neck and thoracic and lumbar spine may develop in patients who have had AS for 20 years or longer. X-ray films of the spine may show a fused spine, also known as a bamboo spine. Even though the fusion or the flexed posture is not reversible with the use of TNF-α inhibitors, the pain in the spine and joints still can be improved because there is always some ongoing inflammation.17

A physician should not hold off on giving patients a biologic agent because of the notion that the disease is too advanced. The flexed posture certainly places the patient at risk for falling and interferes with normal day-to-day activities, but various operative techniques have evolved and improved over time to correct these abnormalities.18 After the degree of the flexion deformity is estimated, various combinations of osteotomies may be performed that will correct the degree of flexion deformity measured. The 3 operative techniques that have been described to correct thoracolumbar kyphotic deformity resulting from AS are opening edge, polysegmental wedge, and closing wedge osteotomy.

More diagnostic clues

Primary care physicians should strive to identify patients in their practice who have IBP and assess their risk for AS and the related diseases. Research designed to develop screening questionnaires for patients with back pain to assess their risk for AS is ongoing. In addition, new genes are being identified that will dramatically alter the current view of the pathogenesis of this illness and provide more diagnostic clues to an early preradiographic diagnosis.

It is hoped that early treatment can prevent the occurrence of the flexion deformities in patients with AS. Whether early treatment with the TNF-α inhibitors will prevent fusion and flexion deformities from developing is uncertain right now. However, it remains intuitive that such dramatic relief of symptoms and improvement of inflammation (demonstrated on MRI) in the early stages of AS should have a downstream effect on disease progression; investigation for proof of this concept is active.

References:

References

- 1. Baker S, Weisman MH. Chapter 1. In: Weisman MH, Reveille JD, van der Heijde D, eds. Ankylosing Spondylitis and the Spondyloarthropathies. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2006:1-5.

- 2. Calin A, Porta J, Fries JF, Schurman DJ. Clinical history as a screening test for ankylosing spondylitis.JAMA. 1977;237:2613-2614.

- 3. Rudwaleit M, Metter A, Listing J, et al. Inflammatory back pain in ankylosing spondylitis: a reassessment of the clinical history for application as classification and diagnostic criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:569-578.

- 4. van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis: a proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:361-368.

- 5. Amor B, Dougados M, Listrat V, et al. Are classification criteria for spondylarthropathy useful as diagnostic criteria? Rev Rhum Engl Ed. 1995;62:10-15.

- 6. Dougados M, van der Linden S, Juhlin R, et al. The European Spondylarthropathy Study Group preliminary criteria for the classification of spondylarthropathy. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:1218-1227.

- 7. Rudwaleit M, Sieper J. A case of axial undifferentiated spondyloarthritis diagnosis and management. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007;3:298-303.

- 8. Dougados M, Gueguen A, Nakache JP, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis: what is the optimum duration of a clinical study? A one year versus 6 weeks non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug trial. Rheumatology (Oxford). 1999;38:235-244.

- 9. Mansour M, Cheema GS, Naguwa SM, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis: a contemporary perspective on diagnosis and treatment. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007;36:210-223.

- 10. Schlosstein L, Terasaki PI, Bluestone R, Pearson CM. High association of an HL-A antigen, W27, with ankylosing spondylitis. N Engl J Med. 1973;288:704-706.

- 11. Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Khan MA, et al. How to diagnose axial spondyloarthritis early. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:535-543.

- 12. Reveille JD, Brown MA. The pathogenesis of ankylosing spondylitis. In: Weisman MH, Reveille JD, van der Heijde D, eds. Ankylosing Spondylitis and the Spondyloarthropathies. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2006:21-37.

- 13. Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium; Australo-Anglo-American Spondylitis Consortium (TASC), Burton PR, Clayton DG, et al. Association scan of 14,500 nonsynonymous SNPs in four diseases identifies autoimmunity variants. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1329-1337.

- 14. Anderson JJ, Baron G, van der Heijde D, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis assessment group preliminary definition of short-term improvement in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1876-1886.

- 15.Stone M, Warren RW, Bruckel J, et al. Juvenile-onset ankylosing spondylitis is associated with worse functional outcomes than adult-onset ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:445-451.

- 16. Hochberg MC, Lebwohl MG, Plevy SE, et al. The benefit/risk profile of TNF-blocking agents: findings of a consensus panel. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005;34:819- 836.

- 17. van der Heijde D, Kivitz A, Schiff MH, et al; ATLAS Study Group. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2136-2146.

- 18. Van Royen BJ, De Gast A. Lumbar osteotomy for correction of thoracolumbar kyphotic deformity in ankylosing spondylitis: a structured review of three methods of treatment. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999;58:399-406.

- 19. Davis JC Jr, Van Der Heijde D, Braun J, et al; Enbrel Ankylosing Spondylitis Study Group. Recombinant human tumor necrosis factor receptor (etanercept) for treating ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3230-3236.

- 20. van der Heijde D, Dijkmans B, Geusens P, et al; Ankylosing Spondylitis Study for the Evaluation of Recombinant Infliximab Therapy Study Group. Efficacy and safety of infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial (ASSERT). Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:582-591.