Tackling football injuries: The lower extremity

Each position in football requires a specific set of skillsand predisposes the athlete to types of injury. Physicians need to recognizeand understand the most common patterns, make a diagnosisand provide treatment based on history, physical examination findings,and clinical acumen-all while recognizing and handling emergencysituations. Lower extremity injuries are the most common footballinjuries. The "hip pointer"may be mimicked by avulsion of thesartorius origin or the abdominal muscle attachments. Muscle contusionscan cause myositis ossificans or even lead to compartment syndrome.Noncontact knee injuries include anterior cruciate ligament(ACL) tears. Injuries to the ACL or menisci have been shown to lead toearly osteoarthritis. Inversion/eversion injuries include ankle fracturesand subtalar dislocations. Practical solutions have been developedfor injury prevention. (J Musculoskel Med. 2007;24:290-294)

ABSTRACT: Each position in football requires a specific set of skills and predisposes the athlete to types of injury. Physicians need to recognize and understand the most common patterns, make a diagnosis and provide treatment based on history, physical examination findings, and clinical acumen-all while recognizing and handling emergency situations. Lower extremity injuries are the most common football injuries. The "hip pointer"may be mimicked by avulsion of the sartorius origin or the abdominal muscle attachments. Muscle contusions can cause myositis ossificans or even lead to compartment syndrome. Noncontact knee injuries include anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears. Injuries to the ACL or menisci have been shown to lead to early osteoarthritis. Inversion/eversion injuries include ankle fractures and subtalar dislocations. Practical solutions have been developed for injury prevention. (J Musculoskel Med. 2007;24:290-294)

Lower extremity injuries are common in football players. Many are noncontact injuries associated with cutting, sprinting, weight training, or overuse; others are contact injuries involving fracture or dislocation. Medial collateral ligament (MCL) tears and thigh musculature strains are particularly common injuries.

Each position in football requires a specific set of skills and predisposes the athlete to certain types of injury that may have different requirements for treatment, rehabilitation, and return to play. For example, injuries that involve the hip and thigh are seen frequently in defensive backs, who make numerous sudden transitions from backpeddling to a closing sprint on the ball. The knee is the single most injured site,accounting for 20% of football-related injuries1; knee injuries are particularly common in running backs. Foot and ankle injuries are seen frequently in offensive and defensive linemen, because massive opponents often roll into their planted ankles. Physicians who treat football players need to recognize and understand the most common and dangerous injury patterns to provide appropriate and effective management.

This 2-part article discusses physicians' sideline management of football injuries. In the first part ("Tackling football issues on and off the field: Upper extremity injuries," The Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine, September 2007, page 393), we described position-specific injury patterns, general management recommendations, and common site-specific injuries in the upper extremity. This second part describes management of the more common lower extremity injuries and offers a practical approach to injury prevention.

SIDELINE MANAGEMENT

To manage football injuries effectively, a physician needs to make a diagnosis and provide treatment based only on history and physical examination findings and clinical acumen, as well as recognize and handle emergency situations that require a higher level of care. Determining if and when to return an injured athlete to play is a key element of the evaluation.

Advance Trauma Life Support protocols provide guidance on trauma management. A primary survey evaluates the injured athlete's airway, breathing, and circulation, and a secondary survey includes a detailed neurological examination (Table), evaluation of breath sounds, a check for abdominal tenderness or distention, and a thorough musculoskeletal examination (eg, palpation of bones and evaluation of joint range of motion). Physicians should look for the "5 Ps" of limb ischemia (pain, paresthesia, paralysis, pulselessness, and pallor) and apply the RICE principle to the acute management of musculoskeletal injuries (Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation).

COMMON INJURIESHip/thigh

Among the traumatic events that involve the structures around the hip and thigh, the "hip pointer" is a common class of injuries that has entered the vernacular. This exquisitely painful entity is a contusion of the anterior superior iliac spine, where the pelvis has almost no soft tissue padding and is vulnerable to injury.

Because hip pointers have an excellent prognosis, only icing and NSAIDs are indicated. They may be mimicked by avulsion of the sartorius origin or the abdominal muscle attachments. Management of the latter injuries also is nonoperative, but a longer period of rest may be required for optimal healing.1,2

Other injuries of the muscle-tendon unit may be acute or acute on chronic strainsplayers may overload a muscle tendon unit, causing a tear acutely, or a chronic injury to a muscle with overtraining of muscles that have not healed completely can prime them for a more clinically significant injury. "Hip strains" generally refers to injury to the iliopsoas muscle, the major hip flexor; "groin pulls" to injury to the adductor musculature in the medial compartment of the thigh; and "hamstring pulls" to strains of the posterior thigh muscles, which are common with backpeddling in defensive backs.

These injuries, and other muscle strains, are managed acutely with RICE. After that, stretching and strengthening are used until the limbs have symmetrical strength and flexibility.2,3

A third major class of thigh injuries is deep muscle contusions, caused by a direct blow to the thigh. These injuries are common but usually only minor, requiring only rest and physical therapy.

More serious muscle contusions may cause bleeding and lead to compartment syndrome (swelling within a tight fascial compartment that is limb-threatening). Deep muscular injury also can lead to myositis ossificans. This intramuscular calcification usually is not functionally limiting. However, it is important in the differential diagnosis because patients eventually may have radiographic findings that appear similar to those of a bone-forming sarcoma and improper biopsy of these lesions has led to unnecessary amputations in young athletes. Trauma to the limb is hypothesized to release mesenchymal stem cells from the periosteum that migrate into the soft tissue hematoma and begin forming bone in much the same way a fracture heals with stem cells entering the fracture hematoma.4

Knee

Football is a game of evading tackles, which requires agility for cutting, pivoting, and running and often results in noncontact knee injuries. Contact knee injuries also are common because the knee joint is more "exposed" than other joints and is a prime target for tackles. The MCL, a common injury site, runs along the medial side of the knee. It keeps this hinge joint from "booking open" with valgus stress, which occurs when a force is applied to the knee that tends to move it toward the midline-a "knock-kneed" position. Injury to this ligament often occurs when a player is tackled or blocked from the side. The player has medial tenderness to palpation, pain with valgus stress, and possibly, depending on the grade of the injury, medial opening of the joint with valgus stress.

The MCL, a common injury site, runs along the medial side of the knee. It keeps this hinge joint from "booking open" with valgus stress, which occurs when a force is applied to the knee that tends to move it toward the midline-a "knockkneed" position. Injury to this ligament often occurs when a player is tackled or blocked from the side. The player has medial tenderness to palpation, pain with valgus stress and,

possibly, depending on the grade of the injury, medial opening of the joint with valgus stress.

Intrasubstance tears (grade 1) or partial tears (grade 2) usually can be managed nonoperatively with a supporting brace and a careful stepwise return to activity. Complete tears (grade 3) often are associated with other knee pathology; usually, they are managed surgically.

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury, quite common in football, has entered the vernacular along with hip pointers. Noncontact ACL tears may occur when a player lands while attempting to decelerate and pivot simultaneously on a nearly extended knee. This is an active area of research; some authors think that the quadriceps muscle, acting through the patellar tendon, may produce an anterior shear force on the tibia that exacerbates the injury.5

Contact ACL injury may occur when a tackle produces a valgus load and external rotation of the femur about a planted foot. Patients classically describe hearing or feeling a "pop." On physical examination, a knee effusion is present. Although patients often "guard" the injury and are unable to relax, a positive anterior drawer test may be achieved with the tibia translating anteriorly with respect to the femur without a solid ligamentous end point. A variation of this test, the Lachmann test, places the knee in 15° of flexion and slight external rotation to relax the iliotibial band. The test is nearly 100% sensitive and specific for ACL tears.

After acute management with RICE, patients typically require radiographs, MRI (Figure 1) and, if the injury is confirmed, referral to an orthopedic surgeon for reconstruction. The best outcomes occur when surgery is performed after the acute swelling has subsided and full range of motion has returned. Although ACL tears were once considered career-ending injuries, modern reconstruction and rehabilitation techniques have allowed many players to regain their previous level of athletic function.

Figure 1 –

This coronal MRI scan shows a fluid signal within a fluid signal within a torn medial collateral ligament (red arrow). (Images courtesy of Dr Alison Toth.)

The menisci, C-shaped cups of fibrocartilage that encircle the medial and lateral tibial plateaus, share the load across the knee joint; their absence has been shown to lead to early osteoarthritis. Although degenerative meniscal tears are common in older patients, even healthy young menisci can become trapped between the femoral condyle and tibial plateau by a sudden shear force that can tear them.

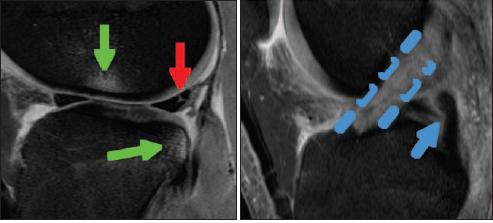

Athletes with meniscus injuries may describe joint-line pain and complain of clicking, catching, or locking of the knee.Tears in degenerative menisci and tears in the inner two thirds of the meniscus, the "white zone" or avascular rim, generally have no healing potential and are debrided with arthroscopic partial meniscectomy. On the other hand,young athletes with simple tears in the vascular, or "red zone," portion of the meniscus may be candidates for meniscal repair (Figure 2). Standard rehabilitation protocols return the player to the field ready to resume play.

Figure 2 –

A sagittal MRI scan shows a fluid signal within the posterior horn of a torn medial meniscus (red arrow). Bone contusions (green arrows) are in a pattern that is highly correlated with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury. In fact,examination of the normal location of the ACL (dashed line) shows only torn fibers when compared with the much darker posterior cruciate ligament signal (blue arrow).

Ankle/foot

The mechanism in which opponents roll into planted ankles can lead to a variety of inversion/eversion injuries, including ankle fractures, subtalar dislocations, and Jones fractures of the fifth metatarsal base. Ankle ligament sprains are common; not all of the soft tissue injuries should be considered benign. Injury to the deltoid ligament or syndesmotic ligament severely compromises ankle stability; complete tears may require operative treatment.

"Turf toe" is a catchall term for a variety of common, related conditions that may result from hyperdorsiflexion at the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint. A variety of injuries at the base of the great toe have been implicated, including tearing of the joint capsule from the metatarsal head, avulsion or damage to the plantar plate, and an osteochondral injury. Acutely, turf toe is associated with subluxation or dislocation of the first MTP joint and sesamoid fractures. Interposed soft tissues may hinder closed treatment. In the long term, hallux rigidus with loss of motion at the MTP joint is a common sequela.

PREVENTION

Injury prevention requires a team effort that starts with coaches,who are instrumental in teaching proper tackling and blocking techniques to avoid unnecessary harm. Trainers contribute to prevention by emphasizing proper stretching,warm up, and cool-down regimens before and after each practice and game and during halftime. For more on prevention, see the Box, "Football injury prevention Xs and Os," below.

Football injury prevention Xs and Os

Research into injury epidemiology and mechanisms has led to the development of practical solutions for injury prevention in football. They include the use of proper equipment, training regimens, and playing surfaces; rule changes; and secondary prevention.

Properly fitting and well-maintained helmets and padding are key to injury prevention. Prophylactic knee bracing may reduce the incidence of medial collateral ligament injuries in linemen, but it has no observable effect in players at other positions.6 Performance of neck rolls and use of supports, in addition to a training program of neck strengthening, reduce the incidence of cervical spine injuries in linebackers.1

The interaction of player and playing surface also plays a big role in injury prevention. Aggressive wearing of "edge-style" cleats has been correlated with a higher incidence of knee injuries7; prewetting artificial surfaces can lower the coefficient of friction and is thought to decrease the rate of lower extremity injuries.1

Rule changes within the past few decades also have made a positive impact. The "spearing" tackle, in which a player initiates contact with his helmet, was banned in 1976, leading to a dramatic decrease in the number of cervical spine injuries.8,9 In 1979, the use of broken or inadequate equipment or pads was outlawed and the "chop block" and tackling by taking an opponent's knees out became illegal. In another rule change designed for safety, plays are signaled "dead" when the offensive player with the ball is clearly in the grasp of the defense.

Athletes have the highest rate of aggravating a previous injury or sustaining a new injury when they first return to play after a period of recuperation. To decrease the injury rate on athletes' return to play, physicians should make sure that patients have equivalent strength and flexibility, with minimal to no pain, when the injured limb is compared with the contralateral limb.

References:

References

1.

Porter CD. Football injuries.

Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am.

1999;10:95-115.

2.

Scopp JM, Moorman CT 3rd. Acute athletic trauma to the hip and pelvis.

Orthop Clin North Am.

2002;33:555-563.

3.

Kirkendall DT, Garrett WE Jr. Clinical perspectives regarding eccentric muscle injury.

Clin Orthop Relat Res.

2002;(403 suppl):S81-S89.

4.

Beiner JM, Jokl P. Muscle contusion injuries: current treatment options.

J Am Acad Orthop Surg.

2001;9:227-237.

5.

Chappell JD, Creighton RA, Giuliani C, et al. Kinematics and electromyography of landing preparation in vertical stop-jump: risks for noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injury.

Am J Sports Med.

2007;35:235-241.

6.

Sitler M, Ryan J, Hopkinson W, et al. The efficacy of a prophylactic knee brace to reduce knee injuries in football: a prospective, randomized study at West Point.

Am J Sports Med.

1990;18:310-315.

7.

Lambson RB, Barnhill BS, Higgins RW. Football cleat design and its effect on anterior cruciate ligament injuries: a three-year prospective study.

Am J Sports Med.

1996;24:705-706.

8.

Waninger KN. Management of the helmeted athlete with suspected cervical spine injury.

Am J Sports Med.

2004;32:1331-1350.

9.

Torg JS, Guille JT, Jaffe S. Injuries to the cervical spine in American football players.

J Bone Joint Surg.

2002;84A:112-122.